(Al Dacascos is the founder of the Wun Hop Kuen Do branch of Kajukenbo and is credited with working alongside Al Dela Cruz to incorporate Northern-style Kung Fu into Kajukenbo.)

Kajukenbo Okayama: Thank you for joining us today, Sifu Al. What are you up to these days?

Al Dacascos: (Laughing.) Trying to relax.

Actually, I retired when I was 65. But it was hard because every time I traveled around people would find out where I’m at and ask me to teach, and do seminars. So here I am, 80 years old, and still doing it.

KO: Tell us about your training history.

Dacascos: Well, I was in Judo/Jiu-jutsu before I even got into Kajukenbo. When I was living on Oahu, I was influenced by my grandfather, who was teaching Pangamot and Escrima. Pangamot is the open-hand style training of Filipino fighting, without the sticks.

At that particular time, the Filipinos on the island of Kauai were considered to be second-class. It was much better to study Judo/Jiu-jutsu, yeah? Until I found out later that the Pangamot, the Filipino style, was much more superior. Because not only were there sticks and weapons, it was also kicks and punches, and also grappling and trapping, yeah? It had a lot of things. It interested me.

Then I moved to the island of Oahu, which is about 100 miles away, and I got more involved. I got into, you know, wrestling, boxing, karate. I got involved in an offshoot of Kyokushin Karate.

And I liked it, because of the“jutsu”…it was Kyokushin Karate but had the follow up of Jiujutsu groundwork. It interested me. And that’s when I met Sid Asuncion.

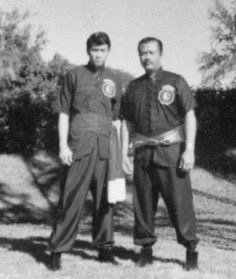

Sid Asuncion (center) with his first two black belts: Al Dela Cruz (left) and Al Dacascos (right), 1962.

Sid Asuncion was the man who really influenced me. He was shorter than I was. But very snappy. That guy had some kind of thing. His techniques would go out 100 miles an hour and snap back at 150 miles an hour. When you got hit, you wouldn’t fly. He would just drop you. He was a very powerful man.

You know, and um…from that, it was Choy Li Fut, a style of Kung Fu, because my neighbor was also into the martial arts. And from there, it just…went.

I had the chance to talk to a lot of professors, and martial artists, you know, in Hawaii. Five minutes of talking to them was more valuable than five hours of physical work. There was so much going on in their words. And because they were here in Hawaii, I could repeatedly go back and forth with them if I didn’t understand, until I got it.

KO: Some people want to know about Wun Hop Kuen Do, and what makes it unique. Can you tell us about it?

Dacascos: Well, one thing I learned from all the professors in Hawaii is that what you learn in Kung Fu is inside here (gestures to his heart). The spirit…it’s here.

(Along with Wun Hop Kuen Do) people also ask me about that spirit. It’s an emotional thing to me.

If I were to say “I love you” to a significant other…that sentence has three meaning. It could be I love you. Or I love you. Or I can say I love you. Or I can also say “love ya”. You interpret each one in different ways, you know. “I love you” (the first one) can sound like I’m being forced to say it. It can sound like I don’t want to say it. If I say “I love you”, you know it has meaning.

Same with any technique, it’s your interpretation. What you interpret, what you pursue…from a different angle, you get a different perception, a different interpretation.

When people ask me “What is Wun Hop Kuen Do” you gotta look at what it is and what it isn’t. It can go many many different ways.

Kajukenbo is Kajukenbo. It was in Hawaii, with Emperado beginning to teach the soft style…He said he was going to call what he did “Tum Pai”. The reason is, he was going through a lot of personal things, back in Hawaii at that time.

Al Dacascos with Ron Lew, Mel Lee, and Dennis Futamase in 1967.

He had a lot of the top Kajukenbo instructors moving to the mainland. It left him teaching more, you know? Being associated with the Chinese Tong society here, he got involved with learning from them. And they told him “if you’re gonna be a total martial artists, don’t go hard. Go hard-soft.”

He kinda took that into his head. He learned some concepts about the soft style, Kung Fu…which really wasn’t “soft”. You learn it soft and take it slowly, but then you take it hard and you go fast. And the speed behind that way of learning was more effective than just learning the hard style.

You had simple motions, you had “V” type motions…many different angles of doing things. A lot of it then was incorporated into what Emperado called “Kajukenbo Tum Pai”. “Tum Pai” meant “central way”. He was going right and left, high and low, and center. That was his interpretation of what “Tum Pai” meant.

I was learning that…Kajukenbo Tum Pai…and then I moved to the mainland. I got involved with a friend of mine that was working at the same place I was working, at an electric company, and he invited me to visit a martial art club they had in San Jose, California. I was sponsored into the club, and that’s where I learned the northern style of Kung Fu. You know, the Shaolin Kung Fu under Wong Jack Man.

The things that I learned…you know, I said “Wow. It’s so much quicker, and so much faster. You can go short distance, long distance. I like that, yeah?”

So I did that for about a year and half, maybe two years. Then Emperado and Dela Cruz came to visit. And I said “Sifu, it’s very difficult for me to say that I’m teaching Tum Pai, because Tum Pai is only one section. Let me demonstrate to you what I have.”

And he saw what I had and he says “I like that. Let’s put it into Tum Pai.”

I said “Then it’s not Tum Pai anymore.”

He asked me “So what do we call it?”

I said we could go back to the traditional Chinese name for Kenpo, coming out of China to Okinawa, “Chu’an Fa”. Which is the same thing as Kenpo (拳法). It translates to “fist way”. (“拳” is the Chinese character for “fist” and “法” is the Chinese character for “way” or “path”.)

Going back to Okinawa in the old days, when you say “Chu’an Fa”, people knew what it was. So Emperado says “Okay, let’s do that.”

So we did that, and I started to teach the Chu’an Fa version of Kajukenbo. But we had been separated, by a couple of years (laughing). Since Dela Cruz was doing a lot of boxing and Emperado was more of an advisor at that time, you could see the split between the Dacascos version and the Dela Cruz version. The version that became more well known was the Dacascos version, in California. The Tum Pai version of Dela Cruz pretty much stayed in the state of Washington and in Hawaii. Here in Hawaii, Dela Cruz had a school that went really big.

If you take a look at the Chu’an Fa here and now, and the Chu’an Fa taught 35 years ago they don’t look the same. It looks totally different. The Tum Pai that was taught originally in California got all screwed up.

Emperado wanted me to teach it to the other four guys that came up at that time: Gaylord, Halbuna, Ramos, and Reyes. But you’ll notice that they were all bigger than me. They were hard stylists. They couldn’t jump the same, they couldn’t sweep. They couldn’t go long distance. And my speed…my speed was really good at that time. They didn’t have any of that. The only guy that was close was Tony Ramos.

But as far as Joe Halbuna, Aleju Reyes, and Charles Gaylord, they couldn’t. They were more power people. So Aleju Reyes said “You guys do the soft style of Kajukenbo. I’m gonna stay with my hard style.” And I understood that, because when you have a lot of black belts under you, and they learn one way, they’re gonna say “What the hell is going on? Now we have to change?” So it was difficult for them.

But for me it wasn’t, because I was just developing my black belt. It was easy for my students to go into it. That’s why Chu’an Fa went that direction, and why we went from the Kajukenbo Association of America to the International Kajukenbo Association. We were never apart though. We were always working together.

The KAA then became Gaylord’s version, or method, of Tum Pai. Which had…which was not the way that it was originally taught.

In Wun Hop Kuen Do, we have “The Red Book”, our collection of our techniques. This book is what makes Wun Hop Kuen Do concrete. It’s…um…it’s a “bible”, you see? When people say do you have anything “concrete”, we can say “yeah we do”. Most of the other guys don’t have their art written down as concretely as we do.

It’s still difficult to say what Wun Hop Kuen Do is. When I say what it is not…I can say at the same time that our Red Book is just the base. It doesn’t mean that you stick to it. You know what I mean?

If you go into the actual (Christian) Bible, you can go to any one phrase…you can come up with 4 or 5 different interpretations. It depends on how you apply it. And that is what we do.

KO: I want to ask you about the spiritual meaning of the acronym, and later about the Eight Mental Aims. First, Kajukenbo as an acronym represents the original arts: Karate, Judo, Jiu-jutsu, Kenpo, Boxing (western and Chinese), but there is a spiritual meaning for the acronym too: “Through this fist art one gains long time and happiness.” (Ka = Long life, Ju = Happiness, Ken = Fist, Bo= Way.)

I can see how “ken” is translated to “fist”, because the “Ken” in “Kenpo” means “fist”. But I can’t see how the others get translated to “long life”, “happiness” and “way”. Where does this acronym come from?

Dacascos: That actually came from Emperado and (Frank) Ordonez. They put it together in a method that uh…I think was kinda half-assed. When they were talking about the original acronym, someone would ask “what’s another way to describe Kajukenbo”? And Emperado and Ordonez would say “Through this fist art one gains long life and happiness”. But it was like…right off the top of their head.

‘Cause, you know, when you take the words (and Chinese characters) themselves “Ka”, “Ju”, “Ken”, and “Bo”, it doesn’t make sense at all. It’s a Hawaiian, made-up name, so to speak.

Touching on the Eight Mental Aims, we also had the eight directions of the octagon. The eight directions for offensive and defensive motion. It can also be interpreted in different ways.

Al Dacascos (left) with Daryl Tyler in Hamburg, Germany, 1976.

So when people say “Through this fist style one gains long life and happiness”, I kinda chuckle. Because the spiritual is on the inside, and based on how you interpret things. Does that make sense?

KO: Oh yeah. I can very easily see the founders pulling it out of their ass.

Dacascos: (Laughing) Yeah, they did.

KO: In our branch, everyone traces the eight mental aims to James Juarez, but he says he got them from you. Can you tell us about those?

Dacascos: Those were based on the eight angles of attack and defense. (Look at the straight lines and the angles of the octagon.) If it’s pointed it’s offense, if it’s flat it’s defense. It was based on that, and is very common in the Chinese art of Pakua/Bagua (八卦), which uses those same angles. (The name of the art, Pakua, uses the kanji “八”, which translates to “eight”, and the kanji for “卦”, which denotes a type of divination.)

When you talk about spiritual meaning, what is spiritual meaning? It’s the hypersonic feeling of emotion.

Let’s look at it in a different way. You’re in a bar, and you happen to see a beautiful lady. You look at her, and she looks at you, and there’s a spiritual, emotional connection. There’s no real meaning until you go up and speak to her. Then it really becomes more emotional and meaningful. Then, the next thing, it becomes physical.

In Kajukenbo, we talk about “mind, body, spirit”. We’re actually talking about “spirit, mind, and body” in that order. That’s how you climb.

The “eight virtues” or “mental aims” is only the beginning, you know? The three main virtues we use are integrity, knowledge, and accountability. That’s also the (spiritual) acronym for the IKA (International Kajukenbo Association). The reason why we did that is because we found that as you get higher in the Kajukenbo ranks, there are a lot of politics going on. And you lose virtue.

You lose respect, you lose humbleness, and so forth. A lot of those people don’t have the necessary knowledge. I look at some of the grandmasters coming up right now, I kinda shake my head and say “Geez, man. Where is this coming from?” And then they take no accountability. They take no responsibility for what they’re doing.

And this is why Kajukenbo, among the other Kenpo arts…sometimes it gets viewed as a joke. You have all these red belts running around…they cannot even do the first four Palama sets! And they don’t wanna take accountability on that. And when you tell them “You need to learn ‘em”, they say “Nah, I got it”.

Where’s the knowledge? That’s one reason I don’t like to use the word “grandmaster”. I prefer the titles of “professor” or “sifu”, because it puts you back in the position of being a “practitioner”.

If you go to a doctor, you don’t see a doctor calling himself a “grandmaster”. A doctor is a practitioner. The only way he gets good, or becomes a professor…he’s always practicing to get better. And better. And better, you see?

Al Dacascos with Adriano Emperado.

When a person has the title of “master” or “grandmaster”, you expect them to know it all. That’s it. And now I see that you have “grandmasters”, and “senior grandmasters”, and “great grandmasters”. I take a look at that and say “What the hell is a ‘great grandmaster’?” I have no idea on that concept, you know?

But the thing is, America is so capitalistic that you always gotta have something to sell. And this is where you lose the integrity of the martial arts.

At my school, when we teach the first eight virtues, we start off with integrity, knowledge, humbleness, respect…but we have a whole list. Three hundred sixty-two of ‘em. Enough for the whole year, and we hit one every week.

Virtue is what makes a man. It’s what makes an adult. It’s what makes you a total being, you know?

And that is why a martial artists can beat you without even fighting, because they understand the virtues.

KO: You’ve mentioned a bit on Kung Fu’s influence on Kajukenbo already. Is there anything else you would add?

Dacascos: Yes. If you understand the concept of the yin-yang, you’re gonna understand more about what I was talking about.

As an example, if he goes high, I go low. If he goes low, I go high. If he goes fast, I “slack”. And if he goes slack, then I go fast. You never fight strength against strength. It’s always strength against weakness.

KO: So, you feel the Kung Fu brought more of that thinking into Kajukenbo?

Dacascos: Yeah, But the thing is, not all Kung Fu is the same. There’s many different versions. It’s like, uh, going to a Chinese restaurant, and they’re serving cake noodle. Some cake noodle is so great. Others taste like shit. Looking at Kung Fu, you’ll find out what works for you. And it’s all individually based.

KO: What are your hopes for Kajukenbo in the future?

Dacascos: Right now, there’s a lot of politics going on with the KSDI and BOA, yeah? It seems as though everybody is promoting everybody. That’s gotta stop somehow. When I started forming the IKA again, and that’s something we’re still in the process of forming…I’m gonna talk to members of the KSDI board and the BOA about it soon…some of the people were saying “What are you doing?” I tell ‘em “I’m doing it for the acronym.” Integrity, knowledge, and accountability.

Take a look at the high ranking belts flooding the system. Some of them deserve it. But for a bunch of ‘em, it’s more of a self-serving thing for the guys who want to be or continue to be “great grandmasters”. I take a look at a lot of these guys…a lot of them were brown belts and green belts when Dela Cruz and I were 5th degree black belts. So I think “these guys don’t know shit about what they’re talking about”. They weren’t involved with the beginning, they weren’t involved with what Gaylord, Halbuna and Reyes…what we were trying to accomplish. They’ve just kind of destroyed the core of what we were doing. I want that to be fixed.

Bring it back into our heart. That’s what the “spirit” was from.

Al Dacascos (right) with his son, Mark Dacascos.

KO: Are there any martial artists that you look up to or looked up to?

Dacascos: That’s really difficult to answer, because there’ve been many. You know, the Hawaiians have a saying: “All knowledge doesn’t come from one school.”

Bruce Lee though. When Bruce and I had our own confrontation, I became sort of like a mentor to him, and he became a mentor to me. Because we had different ways of approaching things. But he made me see things that made me better.

Bruce was two inches shorter than I, yeah? So he had speed. Good with his hands. But his legs weren’t fast. My leg speed was much better than his. There were things that he borrowed, that he used in Enter the Dragon, that were my techniques. I was the only person doing them in Oakland, California. I did it in demonstrations.

I see it in the movie and say “Whoa! There it is! I see it!”

I like the way he did his backfist. And then I improved on it. I took what he had and I made it mine, by improving on it. His backfist was…well, it was based on something called “independent movement”. I teach that as well. It’s one of our fighting principles, which we have 25 of.

It’s the way you move your shoulder, the way you tilt your body, the way your technique goes in and out. Most backfists though, go in a sideways, quarter-circle motion forward. My backfist doesn’t go that way. It goes in a straight line and then cuts in.

The end result: it looks like a back fist, but it was not. It’s a straight punch, straight into the head. People say “Wow, that was a pretty quick back fist.” I say “Thank you.” But they don’t understand that when you go in a circular motion forward, you lose a lot of time. Instead, go straight in and tilt in the shoulder.

It’s what we call “P&P”. “Placement and penetration.” It’s how you place your body and place your technique. That’s what makes a technique effective.

KO: Do you have any advice for Kajukenbo practitioners or martial artists in general?

Dacascos: Make it your own. You know, martial arts is like your signature. You can have a teacher teaching you how to do blocks, and scripting everything. But that’s not you. You wanna make it for yourself. If it’s artistic, fine. If it’s all straight line, fine. The thing is, it becomes you. And that’s just what it is.

You know, I do Wun Hop Kuen Do, and I teach seminars. Then I see people a couple years later. And they kinda move like me, but it’s not exactly me.

They say they’re trying to be like me, and I say “Don’t. Don’t do that. Be yourself.” When I teach them “how” to do it themselves, they become better. It’s not “what”, it’s “how”. “What” you do is not important. It’s “how” you do it.