Kajukeno Okayama: Tell us about yourself.

James Juarez: My name is James William Juarez, age 69, born in Oakland, California. Moved to San Leandro when I was about 5. Right now I’m retired, but I started working in different jobs right out of high school. I hired on at this glass plant and went through a four-year apprenticeship program for millwright work, meaning everything from welding and plumbing and brickwork to all kinds of stuff. I stayed there for about 18 years. They closed down (in 1990), and then I found another job as a millwright. This company needed a welder, so I got in on that. Was there for 27 years and just recently retired.

KO: What’s your history with the martial arts and Kajukenbo?

Jaurez: I’ve been in the arts for…more than 50 years. Started when I was about 12, 13 years old. The only instructor I’ve ever had that I call “my instructor” was Grandmaster Gaylord. I’ve trained with a lot of people during seminars and things like that. But the only “master” I’ve ever had was Grandmaster Gaylord.

Actually, I got into martial arts because of a television show. I saw the Ozzie and Harriet Show, where the two brothers…one got into Judo and one got into Karate, and Karate seemed like a good thing to do. So I went around and checked all the schools that were available to me. There were some Judo schools in Oakland…then I stopped into Gaylord’s school, on East 14th Street, just beyond 150th Ave.

The building had two doors. One opened up to his school, the other opened up to a bar. Sometimes the drunks made a mistake and came in the wrong way. That was interesting.

The workout area was right next to the visitors’ chairs…you know, the little bench visitors sat on if you wanted to watch the class. While they were working out I felt the wall, and the walls were wet with condensation from the workout. I thought “Hm. This feels like home.” That thrilled me. Every other school I’d gone to was…pristine. It didn’t feel right.

So I jumped in on that.

That was 1963 I think. I got my first degree black belt in September of ‘68. I’ve been training ever since.

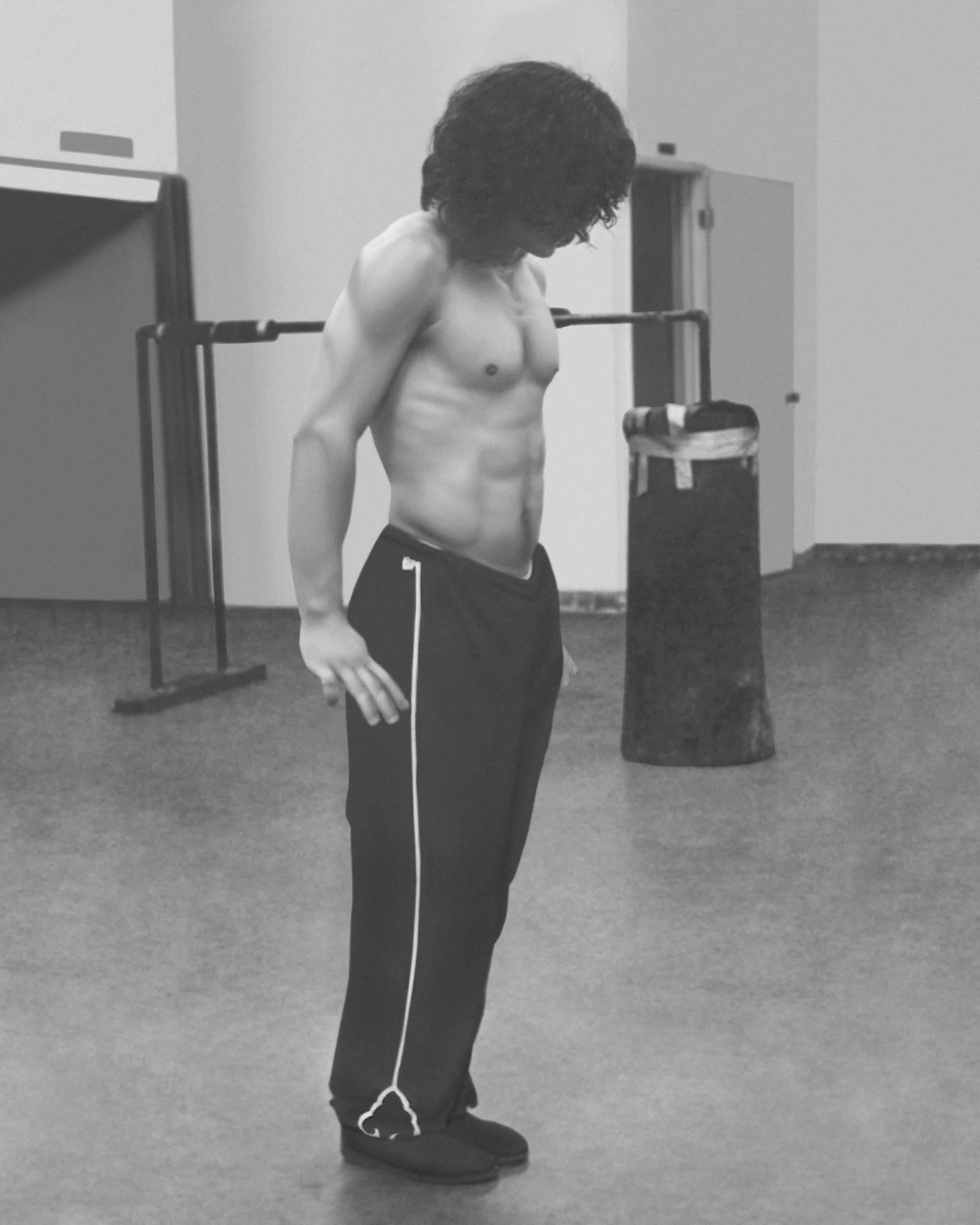

James Juarez, circa 1973.

KO: How did your parents feel about you getting into the martial arts?

Juarez: Actually, my mom, as I got higher in the ranks, started treating me like a monk, y’know, like a doctor. She would come and ask me questions about this or that. I’d say “Mom, that’s more information than I have.”

But my father was always trying to get me into something else. He even offered golf, as an example. “You should take up golf. Maybe make a career out of that.”

Oh well.

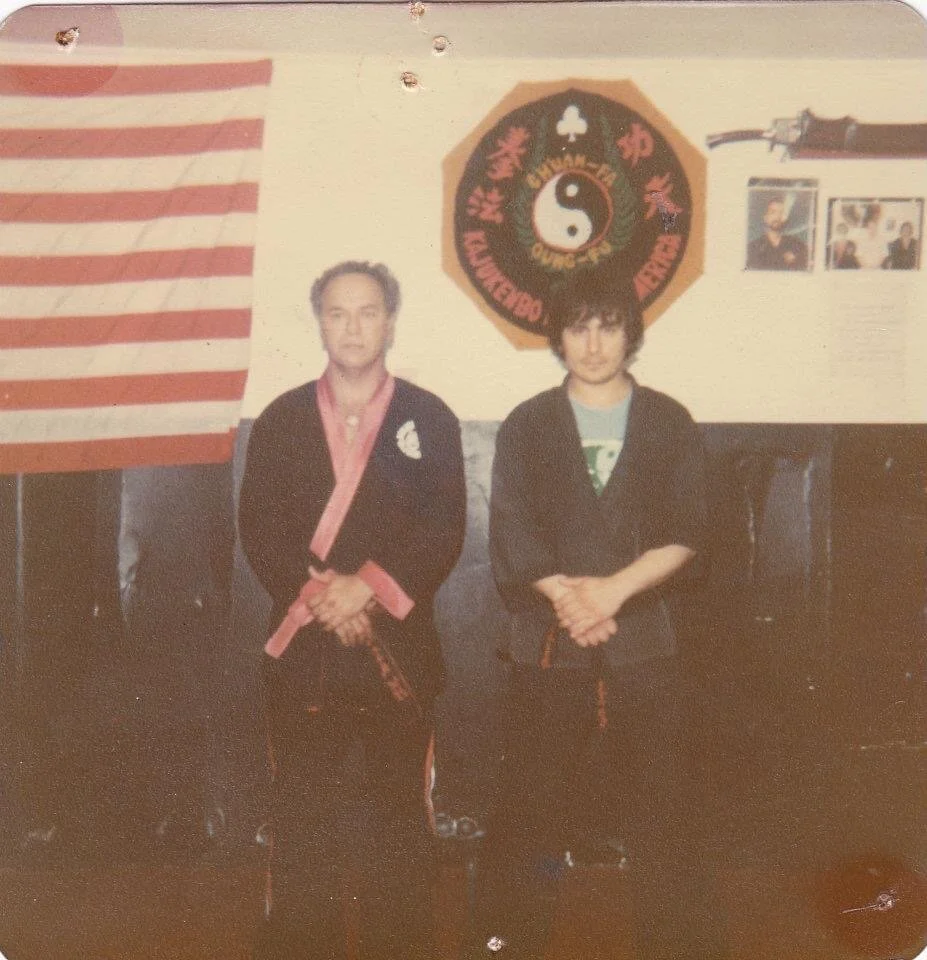

James Juarez (right) with Grandmaster Charles H. Gaylord sometime in the mid-1970s.

KO: How do you think Kajukenbo has changed over the last 50 years?

Juarez: I think it’s techniques have become a lot clearer. And the range of techniques has increased.

When I started, the kicking techniques very rarely reached above the solar plexus. But with our introduction into open sparring, we started touching base with our Korean side, the Tang Soo Do and Tae Kwon Do side. They were kicking high. They were leaving the groin open, but they were kicking high. So we learned to kick high and kick low. That helped us a great deal.

Sifu Vargas also innovated quite a lot, like having us do our forms and punching attacks (combos) on the left side. Learning to use that left side was really important. The first forward attack you have in any of our forms is the forward lunge punch in Pinon 1. It comes off your left hand, right?

If you’re sitting in a car and somebody comes in from the driver’s side you can turn and use your right hand. But if somebody comes in from the other side, you have to use your left hand. That’s what they were trying to teach in Pinon 1: the importance of the left hand.

But we didn’t grasp that right away. Doing forms and punch attacks on the left side forced us to pick up that left side.

KO: I remember you talking about the Kajukenbo guys cutting off the sleeves of their gi tops too.

Juarez: That was to prevent the Okinawan stylists from grabbing our gis and then coming in with a side kick. In sparring, Joe Lewis…his people, people that trained with him, or even people that just watched him would reach out and grab your gi by the sleeve and throw in a side kick, or grab your gi, move your arm out of the way and come in with a punch.

So, we started cutting the sleeves.

A lot of innovation came about from meeting other people. Emperado told me one time that if a man hits you with a technique, you should learn that technique and then learn how to beat it.

But sometimes it was just for comfort, like when the length of the gi pants changed. Ours used to be up just below the kneecap. Basically high water pants. They based that on the Okinawans. The Okinawans didn’t have Nikes, or special clothes when they trained. They came in right off the street to train. Chances are they were fishermen, so their pants were up high. They trained that way and then they left.

As tournaments started up, we started noticing people wear longer pants and they seemed more comfortable, so we went that way.

James Juarez with Grandmaster Melchor Chavez, 2019.

KO: How about changes in the last 20 years?

Juarez: It’s hard to say. Some branches have added theories and systems other than their own, like I did. Some got more into kickboxing, for example.

I see some changes in the way their students perform forms…for the good, for the bad…a lot has changed. Some people have changed the forms to make them more tournament-oriented. They “hollywooded” them up a little bit. Sometimes too much, in my way of thinking. They don’t understand what the forms were originally for, so it takes some of the effectiveness away. But it looks pretty.

But the core of the Kajukenbo system has basically stayed the same.

KO: How do you feel about people quoting your Juarezisms?

Juarez: Well, I don’t own a patent. I wish I did. They’re just things that I felt help people remember things a certain way. They’re old sayings that I learned from boxing school to help me get over certain hurdles. So, I incorporate them in my teaching.

I never say “Okay, this is a Juarezism…” and then say something. I just say it.

To tell you the truth, they are so common to me that I don’t really know which ones they’re talking about. I don’t know what they’re calling my “-isms”. You know what I mean? I didn’t write them down, I didn’t put a patent on ‘em. Whatever people learn from me, God bless ‘em. If it helps your students, that’s what it’s for.

KO: You mentioned some time in boxing. Can you tell me about that?

Juarez: I met a friend that worked at the Left Hook Gym out of Oakland, and he taught some boxing classes on Saturdays, and I would attend the classes, just to see how it could be incorporated into Kajukenbo.

KO: And this was while you were training in Kajukenbo?

Juarez: Yes. I’ve taken courses with other people, attended seminars, several seminars with Sifu Dacascos when he came back from Germany, attended a class with Remy Presas to work the sticks…but I’ve never called any of those teachers my master. My “teacher” was the only one I had. I just studied around to help explain some things that Grandmaster Gaylord wasn’t able to.

KO: How do you feel about the Chinese titles, like “sifu” and “sigung”?

Juarez: Sifu Vargas started getting into the Chinese names in the late ‘60s, early 70’s, and actually I felt pretty comfortable with it. When I first started, Gaylord was called “Chief Instructor”. He was a 3rd degree. The other black belts were “Instructor This” or “Instructor That”. There was never any real “title”, you know what I mean? Sifu Vargas went to different schools and met different people, and those people would say “Who is your Sifu?” or “Who is your Sigung?” and wow…we didn’t know.

So we started using Chinese names. I don’t want to sound too political but, when Grandmaster took the title “Grandmaster”, things changed. We didn’t know what to call the next high rank. Basically, I love the Chinese names because they’re very familial. “Sifu” means “martial art father”, “Sigung” means “martial art grandfather”. The titles, they felt more…tangible.

You don’t feel like you climbed up a mountain to talk to this person. They feel real. You can reach out and touch ‘em.

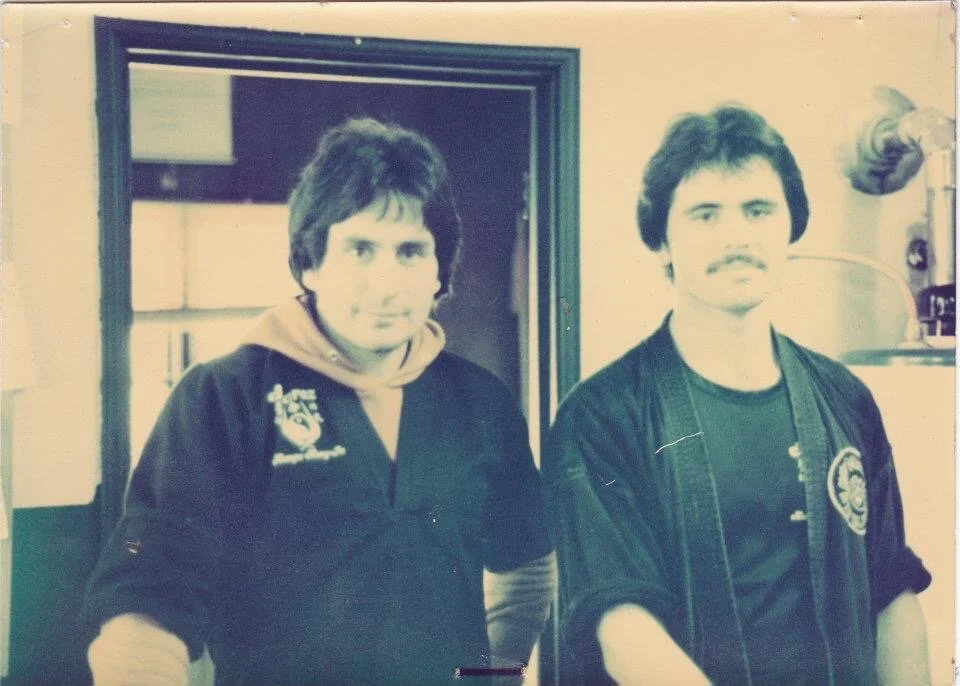

James Juarez (left) with Tom Theofanopoulos, circa 1985.

“Grandmaster”…wow. That’s up there. You think of a grandmaster as someone sitting in a lotus position high on a Himalayan mountain, and everyone’s crawling up to him and addressing him as “Grandmaster”, or “Great Grandmaster”. That scares me to use that title.

But “Grandmaster” is what they’re using now, so we gotta go through with it. You can’t give it back, I guess. I told Professor Gaylord, when he moved me up to (the official title of) Sigung, “If you want me to be next in line, call me ‘Da Sigung’”, which means “Number 1 Grandfather” (i.e. next in line). But it was too confusing. So anyways, we’re at where we’re at.

KO: Are there any stories from history (factual or fictional) that had an impact on your martial arts journey?

Juarez: Well, I always loved the story of the 300 (a.k.a. the Battle of Thermopylae). That’s a classic. But the Japanese had one that was just as important in the study of Bushido and a Code of Honor. It’s the story of the 47 Ronin (赤穂浪士, the “Ako Roshi”). A remarkable story. I was so impressed by how long the warriors had to wait to take vengeance before they attacked their lord’s accuser. I reflect on this story whenever I need courage to go forward with something.

But I think the person that inspired me the most was Musashi. Miyamoto Musashi. Musashi was considered a “sword god” (剣聖, "seishin", literally “sword saint”, an honorary title given to a warrior of legendary skill in swordsmanship). He had so many things going on. I couldn’t believe somebody had lived his life. His book, The Book of Five Rings…it’s kind of like the Bible. It reads like a story, but it’s confusing. But if you have a martial arts problem, you can thumb through the book and then you’ll find the answer. To start from point A to point B and try to remember everything…you can’t do it. You have to have a reason for looking and studying.

One (fictional) book that had an impact on me is a book called “The Ronin”. It’s a very small book. It’s about the growth of a person who starts out like a bully. He does some very vile things. But ultimately he learns a great deal about life.

Also, and this shows that a lot of things influenced me: if you want to study Bushido, or look for examples of it…the movie by Walt Disney (based on the book), Old Yeller.

KO: Everyone traces the Eight Mental Aims back to you. Can you tell me about them?

Juarez: They came from Sifu Dacascos. In one of his handouts for a belt test that I kind of got my fingers on…we used to steal a lot of stuff from everybody whenever we could, because nobody had anything…he stressed the eight mental aims. I studied them and I thought “That’s good. That explains the 8 sides of the octagon, gives the octagon more depth.”

The octagon has a lot of Chinese meanings to it, like representing the elements of nature. But I always looked at it as a way of remembering the 8 mental aims. (Patience, perseverance, belief, honesty, courage, self control, respect for others, love of humanity.) I’ve told students “Use the 8 mental aims as a focus of that octagon. Then you’ll understand”.

In fact, the Kajukenbo patch has a few important symbols in there. I wish people would talk about it more.

KO: Besides Miyamoto Musashi, are there any particular martial artists or fighters that you look up to or used to look up to?

Juarez: One of my classmates was probably one of the best. Rich Mainettei. Rich was one of the top people in the tournament world. I saw him come in as a white belt and work his way up to brown belt. He was gonna go to University and he got promoted to help him spread Kajukenbo when he went. The guy was excellent and created some great fighters, like Barbara Bones.

And there’s always Benny Urquidez, Joe Lewis, Marvin Hagler…a lot of people touched me, and I would go out of my way to watch them perform. They were the top of the list.

KO: Where do you hope to see Kajukenbo go in the future?

Juarez: Without having it change too much I’d like to see it get into the Olympics, but I understand the sport is already taken by Tae Kwon Do. But I’ve seen some of our people fight in the ring, and they do quite well.

Sifu Melchor out of New Mexico proved that he could take a fighter and put him in non-contact, full-contact, kickboxing, and cage fighting. He’s gone the route. Other schools have done that as well. Sifu Tommy, Tom Theofanopoulos, has done a remarkable job with Jiu-jutsu and cage fighting. Ron Esteller has done a remarkable job getting into the schools. I think every kid should learn something of Kajukenbo. I think it’s great all the way around, the way he’s developed kids’ self defense is remarkable.

These guys have proven that our training as a whole prepares you for whatever you’re gonna meet. Or for whatever you want to do. If you want to stay in a particular branch of martial art and do good, then you gotta train their way. But the character and method of training in Kajukenbo blends equally with the different styles.

KO: Why would you like to see Kajukenbo in the Olympics?

Juarez: So the name would be common. You know, right now it’s still…people hear the name Kajukenbo and they go…“Okay…um…yeah, I understand what Kajukenbo is…you must be one of the vicious ones…” or something like that. And although I’m proud of where we came from, our violent background, I think more people would benefit from it if it was toned down just a little bit…just introduced to the students so that if you want to go full contact, you go this way…if you don’t want to go full contact, you go this way…if you just like the art form, you can go this way…you know, it’s a blend.

KO: Do you have any advice for Kajukenbo practitioners or martial artists in general?

Juarez: Just train hard. I’m always reminded of a saying that Sifu Dacascos said one time when he was describing the differences between Japanese styles and Chinese styles and Kajukenbo. He said the Japanese styles train one hit, one kill. The Chinese styles say answer each attack with at least three. Kajukenbo…we believe in hitting ‘em very very hard, many many times. So that’s my advice to the students. Whatever you do, train hard and keep that in mind.

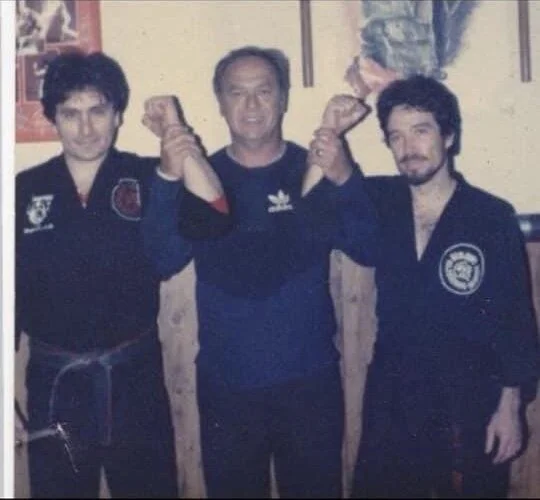

James Juarez (left), with Grandmaster Charles H. Gaylord (center) and Melchor Chavez (right), circa 1980.